tl;dr

We attempted to use fancy data techniques but then reverted to using LLMs to classify our data to make analysis more simple.

Background

Magic Loops are simple programs that combine LLMs with traditional code to make building and running automations both quick and effortless.

These programs, called Loops, can range in a variety of functionality:

- ChatGPT automations

- API endpoints

- Time-based workflows

- Email-triggered logic

- Custom website scrapers

Our users have created over 20,000 Loops (with varying degrees of success).

As people have tried to create new automations, we’ve identified gaps and added new functionality:

- Full request/response APIs

- LLM history

- JSON mode for GPT-4 and GPT-3

- Internet access for Code Blocks

- Advanced web scrapers

- “First-class” data sources (weather, finance, etc.)

- Diff “Blocks” (comparing data across runs)

- Loop “State” via dynamic Variable setting

- Image generation

Even with these additions, there’s still a large swath of missing features.

At first, it was easy to respond to user requests, but as the tool has become more popular, we needed a more scalable approach to analyzing the Loops.

K-means Clustering

One of our users had an interesting Loop request:

Cluster strings using OpenAI embeddings and k-means

Oooh, great idea!

Let’s use k-means clustering to group Loop descriptions and then use that data to better understand what users are trying to do with Magic Loops!

It worked… ish

The Problem

Our Loop descriptions are entirely user generated.

That means you can have a request like:

text me when $TSLA is up more than 5%

And another request like:

track the prices for my favorite stocks and alert me when they change by a certain amount

Depending on the embeddings used, these may get clustered together or they may not.

More importantly, requests that seem similar may be grouped together even if some can be built with Magic Loops today and some cannot.

We needed a better way to understand, and filter, which Loops were possible and which required new functionality.

The Questions

Whenever you try to understand data, especially product or usage data, it’s best to figure out the types of answers you want first.

Put another way: you can find all sorts of useless correlations from aggregates and outliers. It’s easy to get lost in things that seem relevant, but aren’t.

So what do we want to know?

At a high-level:

- Which types of Loops are most popular?

- Which user requests can’t be made with the system today?

- What missing features would enable more Loops to succeed?

- Which Loops are now possible with the recent changes?

Expanding our dataset

Many of the Loops we want to analyze weren’t necessarily possible when they were first created.

We’ve been using some simple SQL queries to analyze things like “what causes this Loop to fire?” and “what APIs does this Loop hit?”, but have started to find false positives and false negatives.

Depending on when the Loop was created, it’s actual contents may be useless or incorrect given the limitations of the system at that time.

First Idea

What if we rebuilt everyone’s Loops, and then saw what succeeded?

Great idea, but that will take awhile!

Second Idea

What if we used GPT-4 to re-classify the initial user requests into structured and actionable data?

Instead of fully recreating Loops, let’s isolate some important facets and then generate a new dataset with those facets?

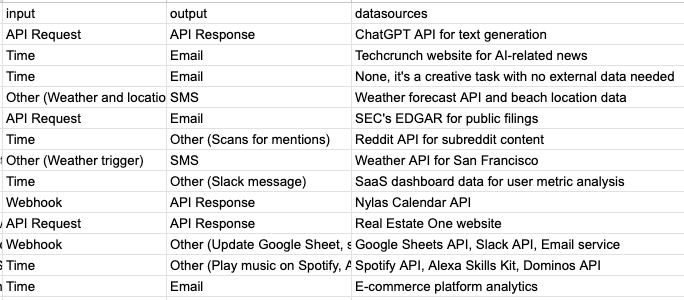

Let’s start with 3 values: “input”, “output”, and “datasources”

ChatGPT, please write a script to… 💡

Using Magic Loops to analyze Magic Loops

We started by writing a SQL query to find unique Loop descriptions (recent users, failed Loops, etc.).

De-duplicated, this gave us a list of ~1600 distinct strings.

From here, we created a Magic Loop to classify descriptions into three fields:

- input

- output

- datasources

This seemed to work well enough, but there were a few obvious issues:

Questions we didn’t know to ask

We made sure to tell our GPT-4 prompt about the various existing “Blocks” within Magic Loops.

If there wasn’t an existing Input or Output Block, we asked it to use Other (w/description).

After running a 100 or so descriptions through, it became obvious that we needed to give GPT-4 more flexibility in it’s responses.

We noticed that it would often use Other for things that were possible, but would lazily say “Triggered based on data change”. This often meant that the Loop should run e.g. every 5 minutes and compare data — once some condition was met, then the Loop would continue.

Great! Let’s give our prompt some more flexibility.

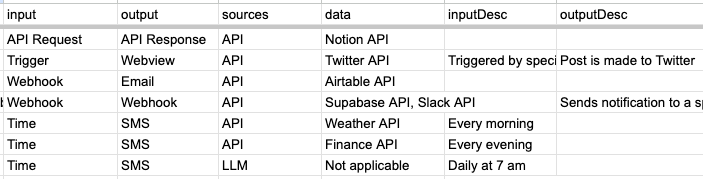

We added a few new types to the input and output options such as “manual”, “trigger”, “webview”, and “file.”

Additionally, let’s add an inputDesc and outputDesc field to give GPT-4 the flexibility of expounding on a specific trigger or file use.

We also split datasources into two fields: data and sources. This should give us a better glimpse into what sort of processing and external resource access each Loop needed.

Much better:

Good old-fashioned pivot tables

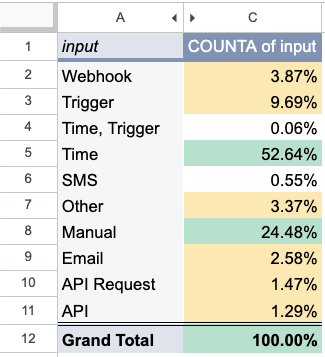

Now that we’ve added structured data for each of the Loop requests, it’s much easier to glean insights about what our users are trying to do.

As an example, it turns out almost 25% of these requests were simply manually triggered and/or one-off tasks:

Looking at the Loop descriptions for these Loops, we can see that some Loops are really meant to just run once! More interestingly, it appears many of these “manual” Loops are actually users trying to test the platform first, and then they presumably would want to automate the result later (e.g. looking up a product price).

Using this data, we can form new hypotheses and improve the product for these flows.

As an example: The Loop Creator should be more iterative, enabling users to “work-backwards” from a result into an automation.

What’s Next

Now that we have a structured dataset, we can use more advanced techniques for understanding user intent.

Rather than using k-means clustering on the whole set, we can instead run k-means on just the data sources, giving us more fine-grained insight into the classes of missing functionality within our system.

We can also set up this Loop in production, such that every new Loop is classified on the fly.

From here we can then provide better feedback to the user on whether the Loop is even possible today, and what changes they can make to get something to work.

The hardest part of writing software is understanding what the end user wants.

Building software that builds software is no easy task, but with the right data in place, we can now increase the capabilities of Magic Loops for everyone.

What are you waiting for? Create your first Magic Loop today!